How did soft light and naturalism co-evolve in early European cinema?

Introduction

This essay is an historical perspective on naturalism and the development of soft light in film. It will aim to investigate the way in which the use of soft light allowed for a more natural and realistic representation of images on screen and how the demand for this kind of image, in turn, pushed the technological advancement and development of soft lighting.

The years spanning 1940 to 1970 will be looked at, as the films made in this period were hugely revolutionary for the use and evolution of soft lighting. It could be argued that it was during this period that some of the most influential movements took place, creating some of the most progressive films in the process. Furthermore, it could be argued that most of the long-lasting changes in regards to soft lighting happened within this period.

To further understand this evolution, the progression and use of soft light will be analysed by looking at key films and contributors from realist movements. As well as this, Directors and Cinematographers who are outside of the movement, who have nevertheless increased the trend to more naturalistic cinematography with a greater use of soft light, and the use of new and at that time unconventional techniques, will also be considered.

To achieve this, early realist movements like Italian neorealism; as well as the movements and directors who furthered the increased stylistical use of naturalism, such as the director Robert Bresson, and the cinematographer Raoul Coutard, within the French New Wave, will also be looked at. In addition, the subsequent integration of more naturalistic cinematography into more mainstream films, during the ‘British New Wave’, will also be explored.

Smaller movements that have used naturalism to great effect, like the director Ingmar Bergman and the Polish Film School movement will also be touched upon.

Although Realist movements are not the intended focus of this essay, they nevertheless play a huge part in the evolution of soft light as cinematographers started wanting more natural looking images to accommodate “Stories that have a general sense of realism – featuring characters and settings that approximate reality – [which] generally demand a naturalistic approach to lighting.” (Nicholson, 2010:197) This closely intertwines Realist movements with naturalistic cinematography.

Defining Terms

In order to clarify, it is important to distinguish between Realism and Naturalism, which are often confounded. A brief explanation of each will be provided.

Realist Movements aimed to depict stories that “project a slice of life” (Hayward, 2017:235), having a political or social lean, often associated with social documentary. They tended to use “non-professional actors”, preferring to “[shoot] in natural light” (Hayward, 2017:235), on location “rather than studio”(Hayward, 2017:235). This is a compressed definition, the extended version is provided by Hayward (2017:235) in Appendix A.

“Andre Bazin, proclaimed neo-realism as a cinema of ‘fact’ and ‘reconstituted reportage’ which rejected both dramatic and cinematic conventions and which 'respected' the ontological wholeness of the reality it captured” (Fellini et al., 1987:4)

Naturalism is a way of portraying the subject as it is seen to be in real life, but not necessarily having a political or social message. Naturalistic cinematography is sometimes regarded as a sub-genre of realism. However, it also stands on its own.

Whilst naturalistic lighting was initially developed in the Realist movements, the trend was taken up and developed on by cinematographers who wanted a more naturalistic image, for stories that did not “focus on social reality” (Hayward, 2017:235) and were not confined to the ideology or aims of the Realist Movements. This was the birth of naturalistic cinematography, which, with time, was incorporated into the mainstream. It was in the quest for naturalism that the techniques of soft lighting, as a means to achieve this, were developed.

For clarity, the term naturalism is used within the context of cinematography, based on the definition provided by Nicholson in his journal article, ‘Cinematography and Character Depiction’. According to Nicholson, "most films occupy a position between extreme naturalism and extreme stylization, being considered as realistic while still incorporating stylistic elements to enhance the narrative, thematic, and aesthetic elements of the story" (Nicholson, 2010:197).

Soft Lighting

While soft lighting is a naturally occurring phenomenon that has been used in cinema since the beginning, the goal behind using it has not always been naturalistic cinematography. How it is used has a great impact on the image, which can result in totally different effects, going from a more realistic look to the opposite effect, which is unrealistic, having no shadows at all.

Fish Tank (2008) is a good example of a naturalistic look using soft light. In Figure \ref{fig:FishTank} we see a room where sunlight and shadows are scattered into the room and one cannot see where the light affecting the subject is coming from.

Fig. 1: Natural lighting in Fish Tank (2009)

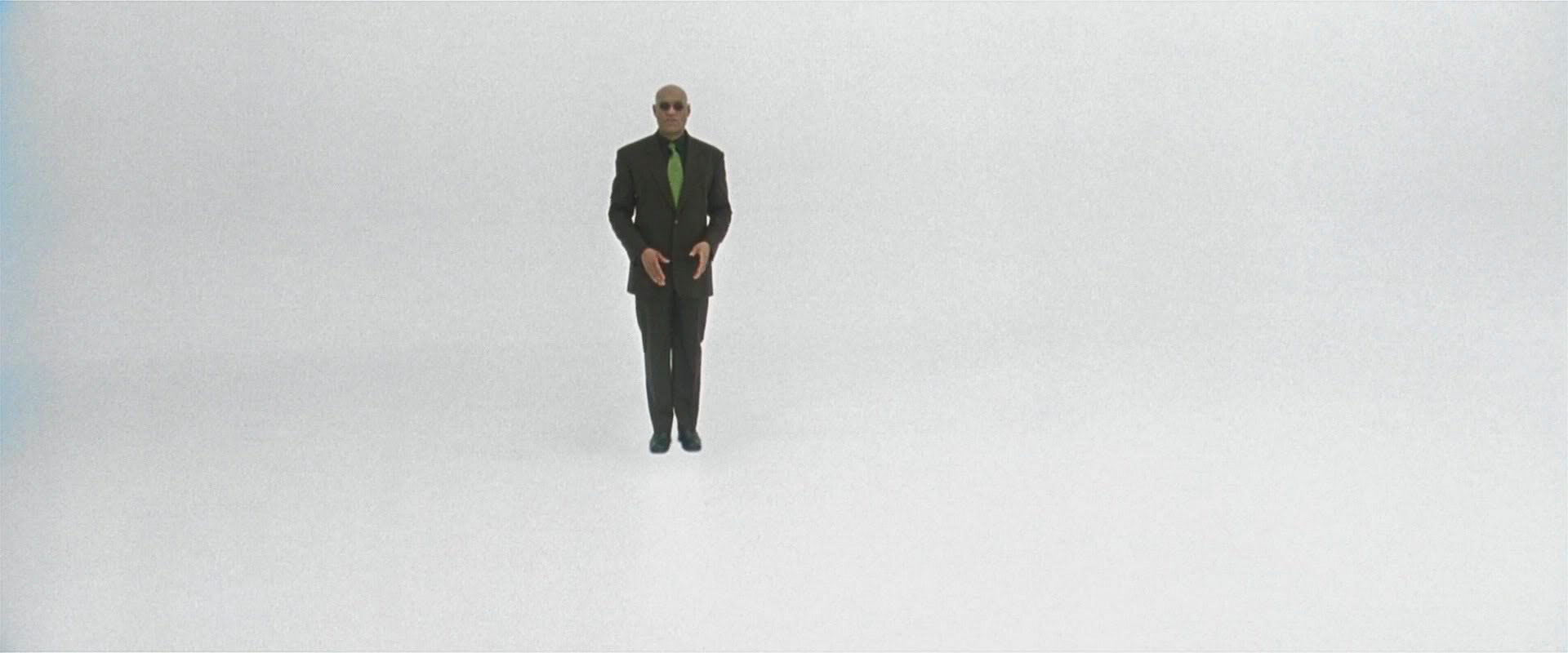

The opposite to this would be The Construct in The Matrix (1999). The sourceless nature of The Construct is a perfect example of how soft light can have the polar opposite effect by having no visible shadows or light source.

Fig. 2: The Construct in The Matrix (1999)

What is Soft Light?

In order to thoroughly understand the history of soft lighting, a comprehensive examination of the techniques used to generate it and its subsequent effects must be conducted. Jay Holben describes this process well in an article from the American Cinematographer entitled Shot Craft: Light Quality 101 (2020). Holben states that "The closer the source is to your subject, the softer the light will be." (Holben, 2020:17). So “When bringing the source closer to the subject — and thus softening the light — you are increasing the source’s size relative to the subject.” As stated by Roger Deakins on his blog, “Softness is determined by the size of the source relative to the size of the subject.” (Roger Deakins, 2018)

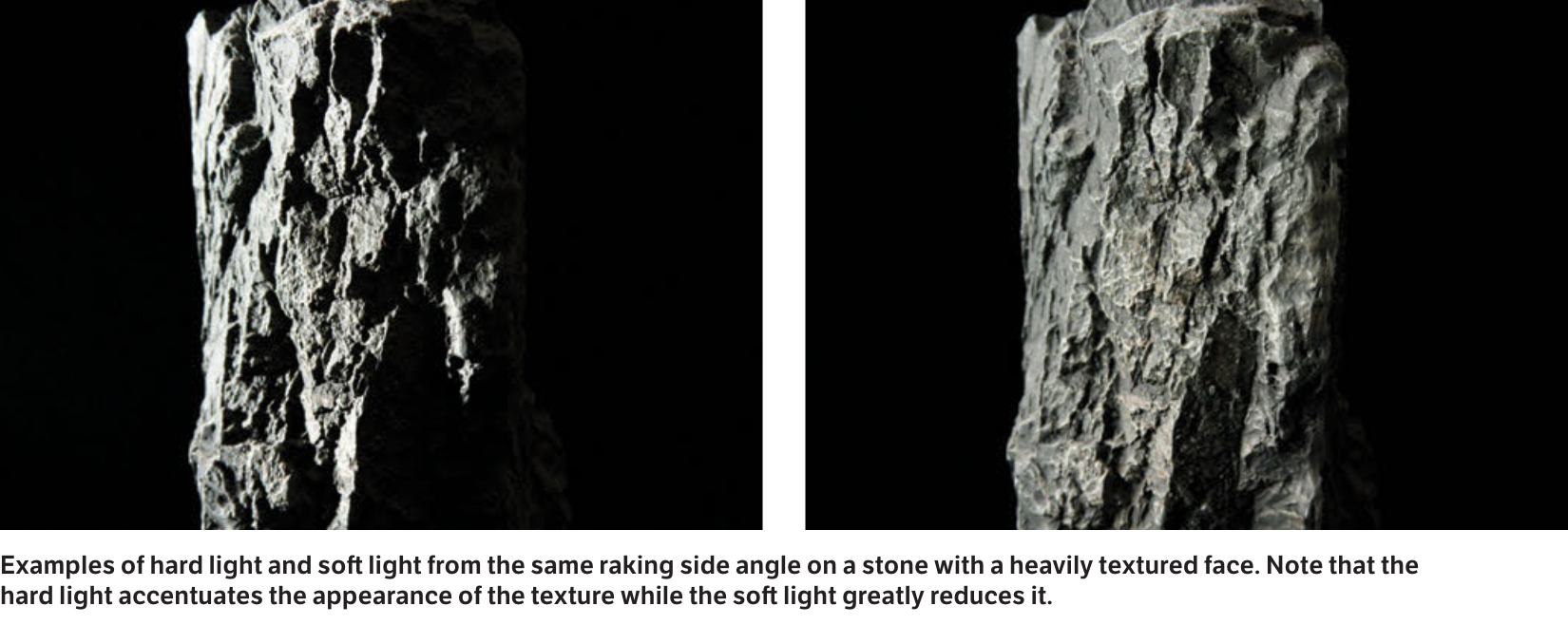

As the light appears less directional and more scattered, it has the effect of lowering the contrast of the item being illuminated; this results in lower contrast as seen in Figure \ref{fig:ASC101}.

Fig. 3: Light Quality 101 (2020)

Light becomes softer as the photons become more scattered, "the shadow transition becomes longer and more gradual.” (Holben, 2020:17). This results in creating a “nearly shadowless environment” (Holben, 2020:17), because of the light being heavily scattered, so that it is difficult to determine where the light originates from.

When discussing soft light the term ‘quality’ is often used to discuss the “nature of the transition between light and shadow” (Holben, 2020:16). Another term to describe the same phenomenon is ‘Fall Off’ also referred to as ‘shadow falloff’. There are two primary ways of increasing the size of the source and increasing quality of light. One of them is photon diffusion, the other is diffuse reflection.

Photon diffusion, also known as ‘through lighting’ or ‘diffused lighting’, works by having a large piece of partially transparent cloth that doesn't absorb all the light, therefore scattering in with a reduction of intensity soft, This can be seen in Figure \ref{fig:Arrival} on the Set of Arrival (2016).

Fig. 4: Example of diffused lighting Arrival (2016)

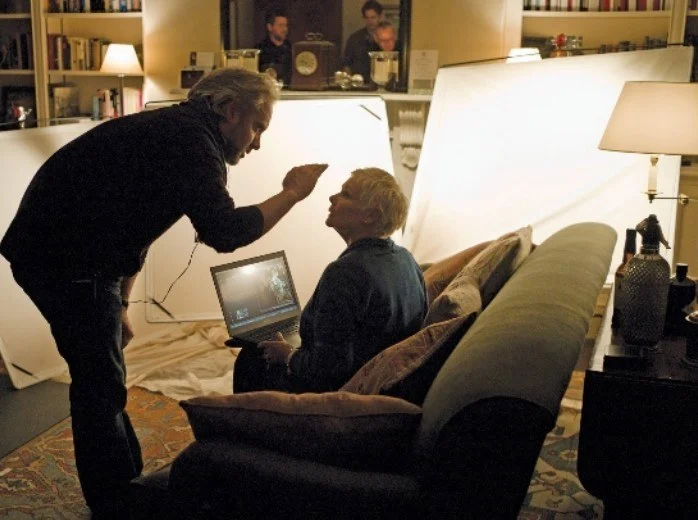

The other way is diffuse reflection, also known as ‘bounced light’. This is where light is bounced into a larger piece of more reflective cloth. Both of these methods increase the size of the light source[^a] therefore softening the light. An example of bouncing light is seen from a Behind the scenes photo from Skyfall (2012) in Figure \ref{fig:Skyfall}.

Fig. 5: Skyfall: MI6 Under Siege Example of Bounce lighting (2021)

One of the main benefits of using soft light for production is that “soft lighting is more generalised in a space allowing actors to move more freely, or for the blocking to be changed at the last minute.” (Mullen, 2012). This “would permit shooting in all directions without having to choreograph the movement and position of the lighting unit, therefore speeding up production.” (Salt 1983:327) Thus faster turnarounds for filming and a more natural performance is possible as the actors is not restricted to their marks.

Other than its benefits to the look of the film, soft lighting produces “more flattering effects” (Allison, 2007) iin facial lighting, as blemishes on the actor’s face are hidden. This is due to the lower contrast nature of soft light. This was especially important during the star system of the 1910’s where it was “ever more important to make the actors look attractive” (Allison, 2007). This was often achieved by bouncing light to “[ensure] there are no harsh shadows on the person or object being lit” (The Foundry, 2020) as seen in Figure \ref{fig:EBounce} where a person can be seen holding a bounce card in the centre of frame.

Drawbacks of Soft Lighting

There were certain technical hindrances that resulted in the slower development of soft light during early cinema. Two of the main factors being the speed of the film stock and the power efficiency of the lights at the time.

One of the inherent drawbacks to using softer lighting is the power draw, - “two to four times the wattage is needed to achieve the same light level on the set as with ordinary direct lighting.”( Salt, 1992:253) This is due to indirect lighting being a “very inefficient method of lighting” (Salt, 1992:253) because of the light scattering by its very nature. To achieve the same luminance or exposure, one has to compensate by either using more powerful lights or faster rated film stocks [^b], which only became available later.

‘Exposure compensation’ is when you either make the lights brighter or you make the camera/film stock more sensitive. This means that as film speeds got faster, less light needed to be used, therefore compensating for the inefficiencies that happen when you soften light.

In the silent era, soft light was achieved by using light fixtures called Cooper-Hewitt lamps as seen in Figure \ref{fig:CH}. They are “gas-discharge fixtures in tubes, a cross between a mercury vapor street lamp and a fluorescent tube, [which] produced a soft light.” (Mullen, 2012). But a lack of efficiency and “Sound killed the use of the noisy Cooper-Hewitts” (Mullen, 2012). They were “replaced by banks of tungsten lamps” (Mullen, 2012), which were more powerful and could achieve the same soft look when directed through “spun glass or silks” (Mullen, 2012). However, the power output they were able to achieve was still inadequate for indirect lighting. One of the main reasons for the shift “from 1.25 kW to 5kW” (Salt, 1992:255) that happened during the late 50s and was “prompted in part by the European use of bounce lighting” (Salt, 1992:255).

Fig. 7: Cooper-Hewitt lamps (2017)

Another issue is caused by the nature of soft light. Due to the increased size of the source, the light becomes less controllable as it scatters everywhere. In a blog post Roger Deakins has stated that “the control of a bounce source is often an issue” (Roger Deakins, 2013) and that he uses “a system of 'louvers' which I create using multiple small flags” (Roger Deakins, 2013), to control the spill off of the light.

As Vilmos Zsigmond ASC states, the use of too much soft light can also result in the image lacking texture and the look “just becomes boring. The difficult thing is really to light softly but to create a contrast at the same time. This is a difficult thing to do.” (Malkiewicz, 2008:85) The overly soft look goes against naturalism, becoming more of a stylised look.

Soft Lighting before Realism

This section briefly examines the use of soft lighting in films that are not considered to be naturalistic, however, still visibly used soft lighting for an alternative effect.

Soft light has been used in cinema since the silent era. Enoch Arden (1911) was one of the first to use “soft lighting on faces as a technique” (The Foundry, 2020). Soft light tended to be used in correlation with “happier and upbeat scenes” (The Foundry, 2020) representing how the character is feeling. Der letzte Mann (1925) was shot by Karl Freund using soft light, long before Italian Neorealism, however, one wouldn't class Der letzte Mann (1925) as being a naturalistic film, - as can be seen in Figure \ref{fig:Der letzte Mann}

Fig. 8: Use of soft light in Der letzte Mann (1925)

It's also important to note that one of the ways naturalism differs from more traditional cinema is with its use of motivated lighting. “Lighting is regarded as being motivated when it accords to the natural behaviour of light.” (Nicholson, 2010:197) This can be achieved by using soft light that matches the ‘quality’ of what it's trying to replicate.

Another way to use motivated lighting is when the origin of the light is coming from a “natural direction” (Nicholson, 2010:197). This does not have to be in every shot, however should be established throughout the scene. One example of this is sunlight, - “sunlight coming through windows ‘sourcy’ light, meaning that it is well defined in its origin” (Malkiewicz, 1986:85).

Realism

The Realist movements were a tremendous catalyst for natural lighting as the aim was to portray daily life as it is. “Since the construction of everyday life depends upon an apparent stripping away of artifice, choices about lighting and film stock aim to replicate the appearance of genres closely associated with the everyday and the ordinary.” (Hallam and Marshment, 2000:126)

Before the main movement that we know of today as Italian neorealism, there were films like Cenere (1917), seen in Figure \ref{fig:Cenere} and Sperduti nel buio (1914). These early realist films used only available lighting to achieve their look. This started to evolve after the second world war, when there was a greater need to tell more socially conscious stories through film.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.45\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2022-12-19 at 14.36.25.png}

\caption{\textit{Cenere} (1917)}

\label{fig:Cenere}

\end{figure}

Italian Neo Realism

This section will examine the impact of Italian Neorealism, which had a major influence upon European cinema, especially on the realist movements such as the French New Wave and The Polish Film School movement. This movement transformed the way in which naturalism was captured on camera, greatly furthering the development of soft light as we know it today.

The focus will be on two significant cinematographers from the 1940 to 1950 time period, - Ubaldo Arata and G.R. Aldo, also known as Aldo Graziati. Both cinematographers have worked on films that had a major impact on the evolution of soft light. The time period represents the peak of Italy’s “socially conscious film makers” (Deakins, 2017). Due to limited resources, these filmmakers often used “existing situations as a backdrop” (Deakins, 2017), which forced them to develop “radically different ways to light and shoot” (Deakins, 2017).

"The working methods of neorealism offered a way to produce films without large financial resources.” (Celli and Cottino-Jones, 2007:71)

Ubaldo Arata

Ubaldo Arata began his career in the film industry as a camera operator and eventually worked his way up to become a cinematographer. His work includes some of the most influential Neorealist films such as Rome Open City (1945), directed by Roberto Rossellini. Arata also worked on more mainstream Italian films like Black Magic (1949) Directed by Gregory Ratoff and starring Orson Welles.

Rome Open City (1945)

Rome Open City (1945), directed by Roberto Rossellini, “was shot in the same way that conventional feature films were shot at the time” (Wagstaff, 2007:100). However, as it was filmed right after the Second World War, the production didn’t have the resources required; for example, “the interiors, mostly shot in a studio…. the filmmakers had no alternative but to use large amounts of artificial light” (Wagstaff, 2007:202). This was a problem as “Arata found himself short of bulbs for the lighting units” (Wagstaff, 2007:100). He was therefore unable to light the film in “his sets in the normal way” (Wagstaff, 2007:100). This resulted in an increased use of practical locations with very limited lighting. Also, natural lighting was used for the studio sets, like the gestapo headquarters.

For a “number of studio-shot scenes, particularly those in the Gestapo headquarters” (Salt, 1992:230) multiple shadows are clearly visible, for example behind the SS Officer in Figures \ref{fig:INT1} and \ref{fig:INT2}. The shadows indicate the use of hard light as seen by the resulting sharp shadow roll off.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\begin{minipage}{0.48\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-05 at 14.31.12.png}%{c.PNG} % first figure itself

\caption{SS Officer sitting at desk in \textit{Rome Open City} (1945)}

\label{fig:INT1}

\end{minipage}\hfill

\begin{minipage}{0.48\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-05 at 14.36.05.png}%{h.PNG} % second figure itself

\caption{Visible Double shadows behind Characters in \textit{Rome Open City} (1945)}

\label{fig:INT2}

\end{minipage}

\end{figure}

\pagebreak

When we contrast the interior scenes to the exterior scenes, it is completely different, - Rome Open City’s (1945) lighting methodology for exteriors is drastically different, being more naturalistic. It was one of the first films of its time to use “ambient light and some ‘bounced’ light for softening or filling shadows” (Wagstaff, 2007:102) for exteriors. This is clearly visible in Figure \ref{fig:EXTOC}. On a typical production during this time, “Large amounts of lighting [would] normally [be] used in exteriors (in Paisà and Ladri di biciclette, for example)” (Wagstaff, 2007:102).

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.5\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-05 at 14.34.03.png}

\caption{Naturalistic Exterior in \textit{Rome Open City} (1945)}

\label{fig:EXTOC}

\end{figure}

When discussing Rome Open City (1945) in Film Style and Technology, Salt states that the film used a “kind of overcast day with grubby natural light that is ordinarily avoided” (Salt, 1992:230).

Arata had a traditional background, meaning he did not want to film the exteriors this way, however, he was limited because of financial constraints. This can be seen in a later film he worked on entitled Black Magic (1949), which had a much bigger budget and was lit in a more traditional manner, with the use of harder lighting.

Although the lighting style of Rome Open City (1945) was out of necessity and may not have been considered beautiful, often being cited as “bland” and “sloppy” (Wagstaff, 2007:102), “Its influence is seen as seminal upon the formation of the French New Wave directors. It has been seen as a spur to the growth of cinema-verité. And neorealism, as a genre, has fairly consistently enjoyed a reputation for marking a decisive change in the evolution of narrative cinema” (Walsh, 1977:13), Jean-Luc Godard stating in a review that “all roads lead to Rome Open City.” (Godard, 1959).

The point being made here is that the move towards more naturalistic lighting was, at this time, unintentional and out of necessity, however it started the ball rolling which was picked up by Aldo - the first to intentionally use indirect lighting to achieve a more natural look.

\pagebreak

G.R Aldo

G.R. Aldo (Aldo Graziati), born in 1905, was one of the most influential cinematographers during Italian neorealism and is thought of as being one of the first to use only soft light to create a natural image. His work most notably includes in Umberto D. (1952), and La Terra Trema (1949).

One source of inspiration for this new style of realism may have originated from photography and photojournalism, as stated by HIll and Minghelli, in their 2014 book entitled Stillness in Motion: Italy, Photography, and the Meanings of Modernity. Here, they raise the point that “the formation of many neo-realist cinematographers in the field of photojournalism or the newsreel should not be underestimated” (HIll and Minghelli, 2014:194).

Aldo started his career as a “professional photographer” who was “self-taught, [he] trained by studying the light of the paintings of Caravaggio and doing an apprenticeship in the photographic studios of Paris, first as a portraitist and then primarily as a set photographer. ” (Hill and Minghelli, 2014:194). Later he shifted his career to become a cinematographer. As Néstor Almendros refers in an interview with Masters and Light, Aldo “came to the cinema not through the usual way of the period” (Schaefer and Salvato, 2013:6). This resulted in his lighting style in film being “so unconventional for the period.” (Schaefer and Salvato, 2013:6). He had the advantage over other cinematographers of having a different perspective on cinematography as “He had not come down the same path.” (Schaefer and Salvato, 2013:6).

In the same interview with Masters of Light, Néstor Almendros discussed the look of Italian films during the neorealist movement referring to the use of softer and more natural lighting. He mentions “Aldo was even before Raoul Coutard in using indirect lighting, using soft lighting” (Schaefer and Salvato, 2013:6).

Néstor Almendros also discussed where this softer lighting style might have originated. “Films of the period like Open City and Shoeshine made by other cinematographers had an interesting look, not because the director of photography wanted it that way; it was due to lack of money.” (Schaefer and Salvato, 2013:5) Almendros goes on to comment that, “I'm sure that if they had given those cinematographers more money and technical support they would have done something very professional and slick. But Aldo knew he was doing something different.” (Schaefer and Salvato, 2013:6,7) Aldo innovated in that space to create his own look and feel.

La Terra Trema

La Terra Trema (1948) was directed by Luchino Visconti using a cast of mostly non-professional actors, - it had a “casting of real Sicilian fishermen and villagers” (Shiel, 2006:13) and was filmed on location, due mostly to the lack of financial resources. However, unlike Rome Open City (1945), La Terra Trema (1948) is “Visually, a very modern movie” (Schaefer and Salvato, 2013:7). The visual “style of La Terra Trema is complex” (Hill and Minghelli, 2014:208), mainly due to “Aldo Graziati’s photographic contribution, which dramatically sculpts each scene through strong contrasts of light” (Hill and Minghelli, 2014:208). This is visible in an exterior scene from La Terra Trema (1948) in Figure \ref{fig:boytera}. It is very challenging to achieve a visually complex look while at the same time maintaining a sense of realism.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.5\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-09 at 10.52.30.png}

\caption{Naturalistic Exterior in \textit{La Terra Trema} (1948)}

\label{fig:boytera}

\end{figure}

When it came to the lighting of La Terra Trema (1948), it was “lit entirely differently, and far better, by G.R. Aldo, with fewer resources than were available to Arata [in Rome Open City]” (Wagstaff, 2007, p. 102). Aldo relied heavily on the use of natural light which was supplemented with soft indirect lighting or shaping the existing light using bounces or negative fill, which is the use of a black cloth to absorb light, with the effect of creating more contrast on the face. Piepergerdes wrote that “The only utilization of artificial lighting occurred during night scenes at sea” (Piepergerdes, 2007:246), this can be seen in Figure \ref{fig:boattera}.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.5\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-28 at 09.19.43.png}

\caption{Artificial night lighting in \textit{La Terra Trema} (1948)}

\label{fig:boattera}

\end{figure}

Aldos innovativeness is seen most of all in the interiors, where the direction of light seems to be justified. For example in Figure \ref{fig:2men}, there is hard sunlight coming through the window, however, this is restrained to a pool of light outside the door. The rest of the interior of the location seemingly doesn't have a source of light.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.5\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-09 at 11.35.36.png}

\caption{Natural Interior lighting in \textit{La Terra Trema} (1948)}

\label{fig:2men}

\end{figure}

Although La Terra Trema (1948) greatly improved upon realism with its skilled use of soft lighting, it didn't get every scene right. Figure \ref{fig:girlonbed} is an example of this. The shadows are aligned in the right direction relative to where the window and door are; however, the ‘quality’ of light isn't quite right. The shadows appear too hard relative to what they ‘should be’. Achieving the right amount of shadow fall off is difficult to accomplish as the cinematographer has to correctly find and match the light source that they are going to use in order to create the right amount of light ‘quality’.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.5\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-09 at 10.55.16.png}

\caption{Artificial Interior lighting in \textit{La Terra Trema} (1948)}

\label{fig:girlonbed}

\end{figure}

Aldo’s unique and innovative use of soft light is the key reason that he became so influential. As a tribute to him, Néstor Almendros a cinematographer who “won [an Oscar] for his exquisite naturalistic photography on Days of Heaven” (Schaefer and Salvato, 2013:5) said that we “really owe a lot to Aldo” following up by saying that “he really was a source of inspiration” (Schaefer and Salvato, 2013:6).

To conclude the section of Italian Neorealism, the full extent of the movement's influence “might be hard to understand now but these films had a profound affect on European cinema. "They inspired the 'French New Wave' of Goddard and Truffaut; the 'Kitchen Sink' realism of the 60's in the UK; the students of the Polish Film School" (Deakins, 2017). This is especially true for the use of soft lighting; it helped to shape the movements that followed and their focus on realism and their rejection of traditional cinematic forms and conventions.

This can be seen in the works of French New Wave filmmakers, such as François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, who were “heavily influenced by Italian neorealism” (Celli and Cottino-Jones, 2007:105) and its techniques and approaches.

\begin{quote}

\centering

\emph{“The drive for greater realism gave rise to the breakthrough films of the new wave that marked the beginning of the new decade.”} (Petrie, 2018:210)

\end{quote}

\pagebreak

French Cinema and its New Wave

In this section, the focus will be on French cinema and the New Wave during the mid 1950s to mid 1960s. France was rife with artistic experimentation, including one of the most influential film movements. The Nouvelle Vague was filled with directors who tried novel ways of telling stories. In the age of experimental auteurs, there were also experimental cinematographers, most notably the likes of Raoul Coutard, Henri Decae and Léonce-Henri Burel.

Although the mid 1950s to the mid 1960s is commonly considered the peak of the Nouvelle Vague, this section will not be limited to just the films from the French New Wave. Whilst the movement was known to use naturalistic cinematography, the cinematographers working on the movement didn't always work on films related to the specific movement. They often worked outside it, while maintaining a similar style of lighting and cinematography regardless of where they worked, like Henri Decaë who worked with Jean-Pierre Melville, as well as Truffaut. Cinematographers weren't always linked to specific film movements but tended to work on projects that they chose based on personal preferences.

Robert Bresson is an example of one whose work was distinctive and falls outside the conventions of the French New Wave. However, he developed his own unique style and approach to cinema and his contributions to naturalism and the development of soft light with Léonce-Henri Burel are far too great to ignore.

The style of Bresson’s films evolved through multiple films and cinematographers, two of the most notable being Philippe Agostini and Léonce-Henri Burel. Agostini “created his ‘soft’ look by exploiting various [camera] filters and gauzes” (Burnett, 2007:221) However, Bresson’s films became more naturalistic with his collaboration with Léonce-Henri Burel.

Léonce-Henri Burel

Like many others in this essay, Burel started out working as an “apprentice photographer” (Nogueira, 1977:18) before becoming a camera Operator and later a cinematographer. Bresson’s and Burel’s most notable collaborations are: Diary of a Country Priest (1951), A Man Escaped (1956) and Pickpocket (1959). All of them are notable for naturalistic lighting. However the most “significant innovations they developed involved bounce lighting” (Burnett, 2007:223) This happened in A Man Escaped (1956), and will subsequently be the focus of the section.

A Man Escaped

A Man Escaped (1956) was shot in a mix between a real location and a studio, as Burel notes in an interview with Rui Nogueira, “[M]any scenes had to be shot in studio sets and these same scenes would begin or end in the real setting of the prison at Lyon” (Nogueira, 1977:19). This meant that the “studio cell [had] to match the lighting of the actual cell at Lyon, but, because the location shots show the prisoners coming out of their cells into the gallery, a ‘correlation’ had to be created between the cell and the corridor” (Nogueira, 1977:19). In order to achieve this, Burel “spent considerable time observing the lighting in the cell and then trying to repeat that light in the studio.” (Burnett, 2007:225)

The problem was that this transition had to feel natural, so in his attempt to emulate or replicate the real world Burel decided to live “dangerously by filming almost without light” (Nogueira, 1977:20), which meant that there was a “relatively narrow range of error” (Burnett, 2007:225). So the challenge for Burel was to match and emulate the ‘fanlight’ [^c] (prison window), seen in Figure \ref{fig:Fanlight}, that was in the real set in Lyon prison. This was to “ensure that the spectator could never say this bit was shot in a studio set” (Nogueira, 1977:19). He set out to accomplish this without “artifice or dramatic effects, in absolute simplicity” (Nogueira, 1977:19).

In an interview, Burel stated that “it would have been ridiculous to show them with shadows, especially as the fanlight is right above them. As you don't actually see it until later, I wanted to suggest that the whole cell was illuminated by this fanlight you hadn't seen but which you would know was there.” (Nogueira, 1977:20) To do this he used bounce light, helping to create a sense of realism in the cell. The light coming through the fan light can be seen in Figure \ref{fig:opposite fanlight}.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\begin{minipage}{0.44\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-25 at 18.53.41.png}%{c.PNG} % first figure itself

\caption{Fan Light in \textit{A Man Escaped} (1956)}

\label{fig:Fanlight}

\end{minipage}\hfill

\begin{minipage}{0.44\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-25 at 19.24.58.png}%{h.PNG} % second figure itself

\caption{Soft light resulting from Fanlight in \textit{A Man Escaped} (1956)}

\label{fig:opposite fanlight}

\end{minipage}

\end{figure}

The use of bounce light was done by throwing “light on to a sort of large white shield” (Nogueira 1998:20), which resulted in the light being reflected ‘on the actors’ “instead of falling directly” (Nogueira 1998:20). This created an “ambiance, an atmosphere, and though directed, came not from a particular point but from an extensive surface” (Nogueira 1998:20). This style of shooting was only possible due to Bresson's directorial style, stated Burel; “Bresson works so much in close-up and because there were never more than three actors in shot. With a big set or a wider field, I could never have done it." (Nogueira 1998:20)

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\begin{minipage}{0.45\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/1T2QVYUX.jpg}

\centering

\caption{Soft sourceless light in \textit{A Man Escaped} (1956)}

\label{fig:sourceless light}

\end{minipage}\hfill

\begin{minipage}{0.45\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/4CIQX8C9.jpg}%{h.PNG}

\centering

\caption{Prison Yard in \textit{A Man Escaped} (1956)}

\label{fig:Prision Yard}

\end{minipage}

\end{figure}

Burel’s use of bounce light was “a technique uncommon for the period” (Burnett, 2007:225). This technique was innovative and “would catch on and be used by Pasqualino De Santis [the] DoP on L’Argent, and [by] Coutard.” (Burnett, 2007:225). It changed how films were able to be lit. In Burel's own words “So I think I was one of the first cameramen to use reflected instead of direct light.” (Nogueira 1998:20)

The New Wave

At the start of the New Wave, directors had “shoestring resources” (Temple and Witt, 2018:155) and at the same time, “increasing availability of new technical resources” (Temple and Witt, 2018:154). So, while there was the need to work quickly and with more “flexibility” (Temple and Witt, 2018:154), to save on expenses, the technical advancements of faster film stocks would make this possible.

\begin{quote}

\centering

\emph{“Budgets were limited, and time was money; natural light changes according to its own uncontrollable rhythms; and location shooting, especially in central Paris, does not lend itself to long preparations.”} (Temple and Witt, 2018:154)

\end{quote}

However, this wasn't always admired by more traditional cinematographers, for example “[Henri] Alekan [who] remained militantly opposed to speed-working and to natural lighting.” (Temple and Witt, 2018:154).

During this time film stocks became more sensitive, which “further freed the cameraman from dependence on spotlighting” (Temple and Witt, 2018:154), thus reducing lighting expenses; and the mobility which the use of softer lights permitted and “which the young directors craved was thus within their grasp” (Temple and Witt, 2018:154). The young directors had the creative vision, however lacked the technical skills to transform their vision onto the screen. “Translating [their vision] into images was still a technical skill, and one which the studio magicians did not necessarily have, and in many cases were not interested in acquiring.” (Temple and Witt, 2018:154) - This is where Coutard came in.

Raoul Coutard

Raoul Coutard was another reputed and influential cinematographer of the time. Like many revolutionary cinematographers, Coutard came from a background of photography. In this case, he was a “photo journalist and war photographer” (Kemp, 2006:36). The films he worked on were wide ranging, going from his work “on Jean Rouch's documentary 'Chronicle of Summer', which was quite groundbreaking in terms of capturing 'realism'” (Roger Deakins, 2017) to his work with Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. Coutard was also one of the first who “really made this naturalistic approach to cinematography his signature 'style'.” (Roger Deakins, 2017) This ‘signature style’ can be seen throughout his work.

Le Petit Soldat

Le Petit Soldat or The Little Soldier (1963) was Jean-Luc Godard’s second film with Raoul Coutard “made in 1960” (Salt 1983:253) although released in 1963 . It was in Le Petit soldat (1963) where “Coutard introduced the practice of bouncing light off the ceiling from rows of photoflood reflector bulbs fastened above the tops of window and door frames, and pointing upwards at the ceiling.”(Salt 1983:253) Part of this lighting rig can be seen in Figures \ref{fig:Photoflood}. This style of light was used to “mimic and boost the natural light coming through the windows” (Salt 1983:253). The rooms were lit to a point where “filming is possible with super-fast stock” without force developing the film (Salt 1983:253).

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.6\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/arton11462.jpg}

\caption{Coutard Standing Behind Photofloods (2016)}

\label{fig:Photoflood}

\end{figure}

This very soft look can be seen in Figure \ref{fig:Lepetitsoldat}. Although the lighting looks almost sourceless in nature, taken out of context, if this shot is seen within the context of the scene, like in Figure \ref{fig:man touching tie}, it is clear that the lighting is motivated and has a directional source, as Bruno Forestier is standing in front of a window.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\begin{minipage}{0.48\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2022-12-01 at 19.11.58.jpg}

\centering

\caption{Naturalistic light Illuminating room in \textit{Le Petit Soldat} (1963) }

\label{fig:Lepetitsoldat}

\end{minipage}\hfill

\begin{minipage}{0.48\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-12 at 16.48.34.jpg}

\centering

\caption{Natural lighting from Blinds in \textit{Le Petit Soldat} (1963)}

\label{fig:man touching tie}

\end{minipage}

\end{figure}

Due to this sourcelessness, the “non-directional nature” (Salt 1983:253) of the light created by Coutard’s use of bounce light, "filming from all directions during a long take [became possible] without the lighting units getting into the shot." (Salt 1983:253). This innovative use of soft bounce light was one of the key stylistic elements of Le Petit soldat (1963) and was taken advantage of with the use of “hand-held moving cameras”. (Salt 1983:253). Coutard continued to use the style of lighting he developed in Le Petit soldat (1963) as can be seen in Figure \ref{fig:Contempt} on the set of Contempt (1963).

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.5\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/rcoutard_lemepris1 (1).jpg}

\caption{Light installation on the set of \textit{Contempt} (1963)}

\label{fig:Contempt}

\end{figure}

\vspace{-0.8cm}

One of the main drawbacks to “this approach to lighting is that it only works well in all-white rooms, particularly” (Salt 1983:253) due to the white paint reflecting the light better and somewhat mitigating the inefficiency of bounce light.

The second drawback, clearly seen in Le Petit soldat (1963), is that the “eyes of the actors are slightly shadowed” (Salt 1983:253), as seen in Figure \ref{fig:Darkeyes}. This is due to the light coming from the top and is caused by “an absence of ‘catch lights’ [/eye light] showing in the actors’ eye-balls, which are those tiny reflections of the light sources which are conventionally considered to give ‘life’ to the actor’s expression in close shots.” (Salt 1983:253). This is normally solved by using a “low-wattage light fixture or white bounce card placed close to the camera [to create] a highlight in the eyes” (Box, 2020:60)

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.5\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-12 at 16.51.44.jpg}

\caption{Actors Eyes are darker in \textit{Le Petit Soldat} (1963)}

\label{fig:Darkeyes}

\end{figure}

\vspace{-0.8cm}

One reason why Raoul Coutard was able to shoot using more natural lighting and bounce light was due to his choice of film stock. Although the specific type of film stock used on the film Le Petit Soldat (1963) has not been substantiated, it is known that in Jean-Luc Godard's first film with Coutard, À bout de souffle (1960), Ilford HPS (400 ASA) was utilised, with a "special development" that increased the film speed to 800 ASA (Salt 1983:253). This process provided an extra stop of light, which was critical in Godard's desire to shoot all the scenes on location using available light (Salt 1983:253).

The French New Wave became immensely popular, and Raoul Coutard was the central figure who brought about “these radical changes” (Salt 1983:253), towards more naturalistic cinematography, mainly with his use of bounce lighting. Soon these new techniques were adopted in Europe, and “towards the end of the ’sixties, began to have their first effects on American lighting.” (Salt 1983:253)

British cinema

This section will focus on the utilisation of soft light and naturalism in British cinema from 1960 to the 1970s. The increased adoption of naturalism in mainstream cinema will be examined, as well as the impact of technology on soft light. The demands from cinematographers for a more natural image resulted in the development of more powerful lighting equipment.

Lighting Technology

Naturalism could only really be achieved when there were technological developments that enabled cinematographers to create soft lighting. This however required a financial incentive which came as Naturalism started to take a hold in commercials. “It was the demands of such [commercial] cinematographers for a softer look” (Deakins, 2017) which was what “influenced what the film equipment manufacturers” (Deakins, 2017) produced. This resulted in “The development of Space Lights” (Deakins, 2017) as well as more efficient Hard lights like HMIs that could be softened.

\vspace{-0.4cm}

Space lights

\vspace{-0.4cm}

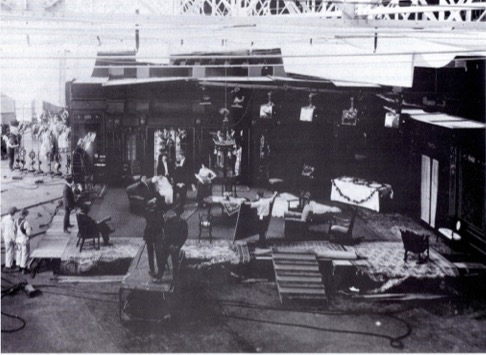

Oswald Morris is one of the only people in this essay to have come from the traditional studio system. He is known for utilising “a mix of old-school hard light and more modern soft-light techniques” (Mullen, 2017). It was his collaboration with director Carol Reed on the film Oliver! (1968) that brought him to prominence, and his lighting techniques were instrumental in defining the visual style of the film.

It was “Ozzie Morris who first asked for that kind of soft lighting on Oliver! and … a wonderful electrician called Bill Chitty designed them” (Williams, 2008). Space lights were extremely economical in how they created soft light. They were “like a giant [silk] dustbin with five or six quartz bulbs shooting downwards… with silk underneath so no hard light escaped.” (Williams, 2008) This created “a good exposure and also very soft light, shadowless light” (Williams, 2008). Hanging from a grid on the roof of a soundstage, they provided an ambience and a “general fill throughout the set as opposed to the fill specifically for the actors’ faces.” (Box, 2020:67)

The soft light they are able to distribute throughout large spaces meant that they were the perfect solution for when “directors and cinematographers demanded their large interior stage sets looked real.” (Deakins, 2017). The first lighting rig to include the use of space lights done by Ozzie Morris can be seen in Figure \ref{fig:Space lights} on the set of Oliver! (1968). The resulting image can be seen in Figure \ref{fig:Oliver}.

\vspace{-0.8cm}

\begin{figure}[H]

\begin{minipage}{0.3\linewidth}

\vspace{0.65cm}

\includegraphics[width=115pt]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screen-Shot-2017-06-28-at-6.20.28-PM.png}

\vspace{16pt}

\caption{Space lights on the Set of \textit{Oliver!} (1968)}

\label{fig:Space lights}

\end{minipage}\hspace{-4cm}\hfill

\begin{minipage}{0.69\linewidth}

\includegraphics[width=319pt]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/JAS8DVNJ.jpg}

\centering

\caption{\textit{Oliver!} (1968)}

\label{fig:Oliver}

\end{minipage}

\end{figure}

\vspace{-1cm}

HMIs

The invention of HMIs (Hydrargyrum Medium-arc Iodide Lamp) was driven by the “demand for ever larger sources of light that could be softened down or bounced to appear more naturalistic.” (Deakins, 2017). As a result of the increased efficiency, HMIs are able to produce “almost four times the light output as a tungsten light of the same wattage” (Box, 2020:146) HMIs had the added advantage of being daylight balanced lamps, which meant that with the advent of colour, they became very useful, particularly because they were not as “hot as the tungsten equivalent” (Box, 2020:146), which prevented gels from burning out, and also because, as they were daylight balanced they could supplement daylight.

During this period there were a few new lights, one that was popular at the time was the ‘soft lite’ (also known as the North Light). “These soft lites were first marketed by Colortran”. The resulting “light [that] emerged from the front opening of the box [was] a non-directional glow: indeed very like the light emerging through a north-facing window of rather small size.” (Salt, 1992:255) (The full technological description of this light is in Appendix B.). Soft lite seen in Figure \ref{fig:soft Lite} in an ad from ‘Journal of the SMPTE’ (Latta, 1968:550)

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=140pt]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-27 at 18.38.32.jpg}

\caption{Colortran Advert in Journal of the SMPTE (1968)}

\label{fig:soft Lite}

\end{figure}

Film Speed

Another invention that might not be directly linked to the development of soft light, but which is very much correlated to the use of soft lighting, and greatly influenced the growing trend of naturalism, was the increase in film speed. As mentioned earlier, to compensate for a lack of exposure you either make the lights brighter or you make the camera/film stock more sensitive. “These [faster] stocks allowed cinematographers much greater latitude when using natural light sources on location.” (Petrie, 2018:210)

There were really fast film stocks during the 60s, Raoul Coutard, as previously mentioned, used Ilford HPS (400 ASA) and pushed it to 800 ASA. For that time HPS was the only stock capable of shooting that fast, however, this slowly became standard when, “in 1962 Ansco put out Hypan (200 ASA)” (Salt 1983:253) and in 1964 Kodak caught up with ‘4X’, which had a speed of 400 ASA.” (Salt 1983:253). The increased speed of black and white stock meant that cinematographers could utilise more natural lighting and then supplement it using softer less efficient light sources.

Whilst the Black and White stock speeds were relatively fast, the newly emerging colour stock remained slow. “Eastmancolor 5251, introduced in 1962 [which] rated at just 50 ASA” (Petrie, 2018:213). This meant that cinematographers had to make the choice to either shoot using more traditional means in colour or shoot using the newer, faster black and white stock. “This was to remain the standard until the appearance of Eastmancolor 5254 in 1968 doubled the speed to 100 ASA.” (Petrie, 2018:213)

Walter Lassally

During this time period there was a shift from Black and White to Colour which had a huge effect on the lighting used, transitioning “from hard-edged, high-contrast lighting to a softer, more diffused use of illumination” (Salt, 1992:255). This happened due to “developments in other creative spheres including television, advertising, fashion, fine art and pop music.” (Salt, 1992:255).

Walter Lassaly was known for his “major contribution to the development of British cinematography with his work on Tom Jones” (Salt, 1992:255). Tom Jones (1963) was shot on a colour stock called “Eastmancolor 5251…. and rated at just 50 ASA” (Petrie, 2018:213), which is far slower “in comparison to black-and-white stocks ” (Petrie, 2018:213).

The decrease in film speed “did not rule out flexible location shooting, more lighting was required to achieve a suitable exposure, particularly in the interiors” (Petrie, 2018:213), Figure \ref{fig:Tom} is an example of the usage of motivated naturalistic lighting to illuminate an actor and the surrounding scene, which was made possible due to the increase in lighting technology at the time. Yet it was still “a major risk, as the cinematographer acknowledges” (Petrie, 2018:213) due to the lack of exposure.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.6\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-02-04 at 23.34.48.jpg}

\caption{Motivated lighting in \textit{Tom Jones}. (1963)}

\label{fig:Tom}

\end{figure}

\begin{quote}

\centering

\emph{“One of the most striking features of British films during this period is the transformation in visual style: from a predominance of black and white to the ubiquity of colour; from hard-edged, high-contrast lighting to a softer, more diffused use of illumination”} (Petrie, 2018:205)

\end{quote}

David Watkin

Unlike Ozzie Morris, David Watkin developed his skills while “shooting industrials, documentaries, and commercials” (Mullen, 2017). He joined the “British Transport Films in 1949” (Petrie, 2018:214), and “It was during this period that he developed an inclination for a particular style of illumination:” (Petrie, 2018:214) He “thought an interesting way to light interiors [would be] to use reflected light.” (Petrie, 2018:214) He then went on to work on “television commercials in 1960” (Petrie, 2018:214) where he met Richard Lester and further developed his “key innovations in soft lighting” (Petrie, 2018:214).

When asked in an interview how he came to explore soft light, David Watkin responded that it was “Partly as boredom relief!” (Petrie, 2018:214). He began to experiment in the shooting of “one scene in a documentary with a housewife in Welwyn Garden City to aim a brute through the window and light the scene with reflected light, which looks better and is more natural if you know what you are doing.” (Petrie, 2018:214)

Watkin disliked using modern technology like HMIs or Faster film stocks; his “hard-line positions against the tide of certain technical advances (film stocks, lenses, HMI...) were legendary” (Salomon, 2008). Nonetheless, he was an avid user of soft lighting, stating in his autobiography “I liked using soft light because it looks nice and it’s easy.” (Watkin, 2008). Watkin still managed to create a very naturalistic look, which can be seen throughout his films. However, rather than trying for economy and the use of natural light, as was customary at the time [^e], Watkin “sought instead to recreate the conditions of a soft and diffused light, coming through the windows, amid a great fanfare of kilowatts.” (Salomon, 2008)

After working on “a Shredded Wheat commercial” (Petrie, 2018:214) Richard Lester invited David Watkin to work on his next feature, The Knack …And How to Get It (1965), Watkin’s first feature film, which was cited as having a “predominantly naturalistic monochrome look” (Petrie, 2018:215).

On Watkin and Lester’s next collaboration Help! (1965), a Beatles showcase, they moved from shooting black and white to colour, which “facilitate[d] the creation of a more overtly softer and diffused lighting style.” (Petrie, 2018:215)

Marat/Sade (1967)

David Watkin continued to experiment with large diffused light sources for sets in Marat/Sade (1967), directed by Peter Brook. Watkin used “large-area soft lighting” (Petrie, 2018), an influence from “still photography and television commercials” (Salt, 1992:255). Rather than using the newer lighting units, he chose to do this by making “a bank of powerful conventional lights” (Salt, 1992:255), “26 10kW lamps” (Petrie, 2018:215), to create a strong source which he shone “from fairly close range onto a large vertical sheet of translucent material” (Salt, 1992:255) which was either “tracing paper or spun glass” (Salt, 1992:255). He then used the diffuse light “that emerged on the other side, as the sole light source on the scene.” (Salt, 1992:255). The result of this technique is seen in Figure \ref{fig:Marat/Sade}.

\begin{quote}

\centering

\emph{“The soft illumination proved not only conducive to fast and efficient production, but the distortion of the outline of figures when backlit added to the unsettling intensity of the drama's setting in a lunatic asylum.”} (Petrie, 2018:215)

\end{quote}

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\includegraphics[width=0.7\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/__Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-27 at 19.08.16.jpg}

\caption{\textit{Marat/Sade} (1967)}

\label{fig:Marat/Sade}

\end{figure}

This technique of creating a glowing wall “about thirty feet square just out of shot at one side of the set.” (Salt, 1992:255), was similar to what Geoffrey Unsworth used a few years later to “light a conference room set” (Salt, 1992:255) in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), however Unsworth “restricted [it] to window-sized areas in ordinary room sets” (Salt, 1992:255).

David Watkin’s influence in bringing more natural lighting to the mainstream was groundbreaking and as he himself said, “People poured shit on that for about five years and then started copying it!” (Petrie, 2018:214)

Other European Movements and Influences

During this time period, there was a diverse array of directors, cinematographers, and movements that had a significant impact on naturalism in film. However, to cover all of them would exceed the scope of this essay. This section will briefly touch on a couple not mentioned in the main section of this essay, yet particularly influential.

The first is The Polish Film School Movement which emerged in the 1950s, following Italian neorealism and taking inspiration from the French New Wave. It was well known for its focus on realism and social commentary through its storytelling, as well as its distinct visual style. Soft lighting was used to gently illuminate the faces and scenes, giving the films a more human and natural quality. Jerzy Wójcik is most notable for his work on Andrzej Wajda's Ashes and Diamonds (1958).

The Swedish director Ingmar Bergman is another director famed for his use of naturalism in partnership with Sven Nykvist on films like Persona (1966) and Cries and Whispers (1972). Nykvist “revitalized Bergman’s films in the late 1950s and 1960s by replacing the high-contrast lighting and overblown chiaroscuro imagery that had long defined the “Art” in art cinema with a purer, more ascetic approach” (Harvard Film Archive, 2000).

Nykvist’s use of soft lighting is seen in the behind the scenes Figure \ref{fig:bts crys} and the resulting image from Cries and Whispers (1972) can be seen in Figure\ref{fig:Cries and Whispers}.

\begin{figure}[H]

\centering

\begin{minipage}{0.48\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Cries-and-Whispers-1972-copy.jpeg}

\centering

\caption{Behind the Scenes photo on the Set of \textit{Cries and Whispers}. (1972)}

\label{fig:bts crys}

\end{minipage}\hspace{-2cm}\hfill

\begin{minipage}{0.5\linewidth}

\centering

\includegraphics[width=\linewidth]{/Users/marc_nickl/Documents/**Screen_Studies-Year-3/IMG/Screenshot 2023-01-26 at 19.37.01.jpg}

\centering

\caption{\textit{Cries and Whispers}. (1972)}

\label{fig:Cries and Whispers}

\end{minipage}

\end{figure}

Conclusion

To conclude, soft light is produced using various techniques with the effect of spreading the light out and reducing harsh shadows. This creates a more even and natural-looking lighting, which is closer to the way light behaves in real life, thus allowing for a more believable image. The advancement of naturalism in cinema was the catalyst for enormous developments in the technology of lighting. It was soft lighting that allowed for more flexibility on set and created a more natural looking image on screen. The result of this approach helped to bring the audience into the world of the film, making the characters and their stories more relatable and emotionally engaging.

As the trend for a more natural looking image gained popularity through realist movements, there was an increasing demand from cinematographers to be able to create this ‘look’. This resulted in lighting manufacturers developing more powerful lighting units and other methods that allowed for the use of more naturalistic lighting.

There was a significant element of necessity in this evolution. As many of these movements lacked funding and resources, natural light was used more and filmmakers were pushed to seek more innovative solutions to create both, a more natural looking image that suited the stories they wanted to tell, and also made it possible for them to work quicker and more efficiently.

Early cinematographers in movements, like Italian neorealism, used naturalism more out of necessity and primarily used only naturally available light, as opposed to artificial lighting. Later movements, like the French New Wave, were inspired by this look and the same lighting techniques developed primarily due to necessity, were turned into a stylistic choice.

The Auteur Renaissance was one of the first places where naturalism became a desired look, diverging from the look and feel of the studio systems at the time, “particularly Italian Neorealism, the French New Wave, and British Kitchen Sink Cinema.” (Cagle et al., 2014:87) The movements tended to be “characterized by their location shooting and use of available light, producing a deliberate visual contrast to the controlled studio environment and artificial lighting typical of the commercial film of the period.” (Cagle et al., 2014:86)

Alongside the development of stronger lights, the advancements in film speed allowed for easier implementation of soft lighting, as less light was required to get a good exposure when using more sensitive film stock. Looking back we can see how film speed developments and how they are correlated with the use of soft light, heavily influenced the growing trend of naturalism.

Cinematographers generally were not linked to specific movements but focused more on films they liked. This brought diversity and helped spread the use of technology that was originally created to solve a specific need. The same melting pot effect was taking place when photographers transitioned to motion pictures. Skills from different disciplines were accumulating.

From a certain point on, natural lighting gained enough momentum to a point where the benefits to the film production became secondary to the sought after look and feel of the image. A less harsh and more natural-looking image began to be the norm.

While Europe was pioneering the use of soft light for naturalism, “towards the end of the ’sixties, [soft lighting techniques] began to have their first effects on American lighting.” (Salt 1983:253). The Film Makers mentioned throughout this essay were at the forefront of the field, making the increased prevalence of naturalism and the techniques of creating it possible.

In summary, the advancement of naturalism and the co-evolution of soft light was one of the most important milestones in the history of cinema. No other style in cinematography has become so ingrained in the look of our films today. Indeed, these developments in European art cinema have gone on to influence the way the vast majority of films are shot and their look today.

\pagebreak

[^a]: A Light source is anything that emits light, - that can be the primary emitter but can also be a reflection.

[^b]: Faster Film stocks are more sensitive due to the size of silver halide in the emulsion this allows for more light sensitivity with the side effect of having a more grainy image.

[^c]: Burel is talking about the prison window and not a fan with a light!

[^d]: A catch light is usually be created by add a small source of light to give a slight reflection in the eye.

[^e]: “Nestor Almendros excelled at capturing the smallest nuances of natural light with the greatest economy” (Salomon, 2008)

\section{List of illustrations}

Fig. 1 Natural lighting in _Fish Tank. (2009) [Film Still, DVD] In: Fish Tank. London, United Kingdom: BBC Films.

Fig. 2 _The Construct in _The Matrix. (1999). [Film Still, DVD] In: The Matrix. Burbank, California: Warner Bros. Pictures.

Fig. 3 Holben, J. (2020) Light Quality 101, _Soft light in comparison to Hard light. [Figure] In: American Cinematographer 101 (10/11) p.17.

Fig. 4 Example of diffused lighting Arrival (2016) Official Behind the Scenes [Video Still, Youtube] At: \url{https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WhE5KMLgTf8} (Accessed on 4 February 2023).

Fig. 5 Hope-Jones, M. (2021), Skyfall: MI6 Under Siege, Example of Bounce lighting [Photograph] In: American Cinematographer At: https://theasc.com/articles/skyfall-mi6-under-siege} (Accessed on 4 February 2023).

Fig. 6 Salt, B. (1992) American Film Manufacturing Company [Photograph] In: Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis. Film Style and Technology. p.114

Fig. 7 Mullen, D. (2017) Cooper-Hewitt lamps. [Photograph] When did soft light become popular?. At: \url{https://www.rogerdeakins.com/lighting-2/when-did-soft-light-become-popular/} (Accessed on 30 August 2022).

Fig. 8 Use of soft light in _Der letzte Mann. (1925). [Film Still, DVD] In: _Der letzte Mann. Berlin, Germany: Universum Film (UFA).

Fig. 9 Cenere. (1917). [Film Still, DVD] In: Cenere Turin, Italy: Società Anonima Ambrosio.

Fig. 10 SS Officer sitting at desk. (2002) [Film Still, DVD] In: Rome Open City Rome: Excelsa Film.

Fig. 11 Visible Double shadows behind Characters. (2002) [Film Still, DVD] In: Rome Open City Rome: Excelsa Film.

Fig. 12 Naturalistic Exterior in Rome _Open Open City. (2002) [Film Still, DVD] In: Rome Open City Rome: Excelsa Film.

Fig. 13 _Naturalistic Exterior in _La terra trema. (1949) [Film Still, DVD] In: _La terra trema Rome: AR.TE.AS Film, Universalia Film.

Fig. 14 Artificial night lighting in _La terra trema. (1949) [Film Still, DVD] In: _La terra trema Rome: AR.TE.AS Film, Universalia Film.

Fig. 15 Natural Interior lighting in _La terra trema. (1949) [Film Still, DVD] In: _La terra trema Rome: AR.TE.AS Film, Universalia Film.

Fig. 16 Artificial Interior lighting in _La terra trema. (1949) [Film Still, DVD] In: _La terra trema Rome: AR.TE.AS Film, Universalia Film.

Fig. 17 Fan Light in _A Man Escaped. (1956) [Film Still, DVD] In: _A Man Escaped. Paris: Gaumont, Nouvelles Éditions de Films (NEF).

Fig. 18 Soft light resulting from Fanlight _A Man Escaped. (1956) [Film Still, DVD] In: _A Man Escaped. Paris: Gaumont, Nouvelles Éditions de Films (NEF).

Fig. 19 Soft sourceless light in _A Man Escaped. (1956) [Film Still, DVD] In: _A Man Escaped. Paris: Gaumont, Nouvelles Éditions de Films (NEF).

Fig. 20 Prison Yard in _A Man Escaped. (1956) [Film Still, DVD] In: _A Man Escaped. Paris: Gaumont, Nouvelles Éditions de Films (NEF)

Fig. 21 Raoul Coutard standing behind Photoflood lighting. Afcinema. (2023) Coutard, “First Name: Raoul”. [Photograph, Newsletter] At: \url{https://www.afcinema.com/Coutard-First-Name-Raoul.html} (Accessed on 14 January 2023).

Fig. 22 Naturalistic light Illuminating room in _Le petit soldat. (1963). [Film Still, DVD] In _Le petit soldat. Paris, France: Les Productions Georges de Beauregard.

Fig. 23 Natural lighting from Blinds in _Le petit soldat. (1963). [Film Still, DVD] In _Le petit soldat. Paris, France: Les Productions Georges de Beauregard.

Fig. 24 Light installation on the set of _Contempt. (1963). Afcinema. (2023) Coutard, “First Name: Raoul”. [Photograph, Newsletter] At: \url{https://www.afcinema.com/Coutard-First-Name-Raoul.html} (Accessed on 14 January 2023).

Fig. 25 _Actors Eyes are darker in _Le petit soldat. (1963). [Film Still, DVD] In _Le petit soldat. Paris, France: Les Productions Georges de Beauregard.

Fig. 26 Mullen, D. (2017) Space lights on the Set of Oliver!. [Photograph] When did soft light become popular?. At: \url{https://www.rogerdeakins.com/lighting-2/when-did-soft-light-become-popular/} (Accessed on 30 August 2022).

Fig. 27 Oliver!. (1968) [Film Still, DVD] In: Oliver! London: Romulus Films, Warwick Film Productions.

Fig. 28 Latta, J. N. (1968) Colortran Advert in Journal of the SMPTE (1968) In: Journal of the SMPTE 77 (5) p.550.

Fig. 29 Motivated lighting in Tom Jones (1953) [Film Still, DVD] In: Tom Jones London: Woodfall Film Productions.

Fig. 30 Marat/Sade. (1967) [Film Still, DVD] In: Marat/Sade. Warwickshire, England: Royal Shakespeare Company.

Fig. 31 Williams, D. (2018) Behind the Scenes photo on the Set of _Cries and Whispers. [Photograph] At: \url{https://theasc.com/articles/beyond-the-frame-cries-and-whispers}

Fig. 32 _Cries and Whispers. (1972) [Film Still, DVD] In: Cries and Whispers Stockholm, Sweden: Cinematograph AB, Svenska Filminstitutet (SFI).

Bibliography

À bout de souffle (1961) Les Films Impéria, Les Productions Georges de Beauregard, Société Nouvelle de Cinématographie (SNC).

A Man Escaped (1956) Gaumont, Nouvelles Éditions de Films (NEF).

Allison, D. (2007) Lighting technology and film style - Lighting - actor, actress, show, tv, director, name, cinema, scene, role, book. At: http://www.filmreference.com/encyclopedia/Independent-Film-Road-Movies/Lighting-LIGHTING-TECHNOLOGY-AND-FILM-STYLE.html (Accessed 22/12/2022).

Ashes and Diamonds (1958) Studio Filmowe Kadr.

Black Magic (1949) Edward Small Productions.

Box, H. C. (2020) Set Lighting Technician’s Handbook : Film Lighting Equipment, Practice, and Electrical Distribution. Routledge. At: https://www-taylorfrancis-com.ucreative.idm.oclc.org/books/mono/10.4324/9780429422560/set-lighting-technician-handbook-harry-box (Accessed 02/07/2022).

Burnett, C. (2007) 'Muting the image: lighting and photochemical techniques of Bresson’s cinematographers' In: Studies in French Cinema 6 (3) pp.219–230. At: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1386/sfci.6.3.219_1 (Accessed 30/05/2022).

Cagle, C., Dombrowski, L., Schauer, B., Ramaeker, P. and Lucas, C. (2014) Cinematography. (s.l.): Rutgers University Press.

Celli, C. and Cottino-Jones, M. (2007) A New Guide to Italian Cinema. (s.l.): Springer.

Cenere (1917) Società Anonima Ambrosio.

Cries and Whispers (1973) Cinematograph AB, Svenska Filminstitutet (SFI).

Deakins, R. (2017) When did soft light become popular?. At: https://www.rogerdeakins.com/lighting-2/when-did-soft-light-become-popular/ (Accessed 30/08/2022).

Diary of a Country Priest (1951) Union Générale Cinématographique (UGC).

Fellini, F., Bondanella, P. and Gieri, M. (1987) Strada, La: LA STRADA. (s.l.): Rutgers University Press.

Fish Tank (2009) BBC Films, UK Film Council, Limelight Communication.

Godard, J.-L. (1959) 'Étonnant: Jean Rouch, Moi un Noir' In: Jean-Luc Godard par Jean-Luc Godard 1 pp.1950–1984.

Hallam, J. and Marshment, M. (2000) Realism and Popular Cinema. (Illustrated edition) Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Harvard Film Archive (2000) In the Company of Light: Sven Nykvist. At: https://harvardfilmarchive.org/programs/in-the-company-of-light-sven-nykvist (Accessed 30/01/2023).

Hayward, S. (2017) Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts. (5th edition) London ; New York: Routledge.

Hill, S. P. and Minghelli, G. (2014) Stillness in Motion: Italy, Photography, and the Meanings of Modernity. (s.l.): University of Toronto Press.

Holben, J. (2020) 'Light Quality 101' In: American Cinematographer 101 (10/11) 11/2020 pp.16-20,22,24. At: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2455894566/abstract/B4BB106683044E6FPQ/1 (Accessed 02/09/2022).

Kemp, R. (2006) 'The Holy Ground' In: Film Ireland (108) pp.36–37. At: https://www.proquest.com/docview/194680383/abstract/707B5F93D9744AFPQ/1 (Accessed 09/01/2023).

La terra trema (1949) AR.TE.AS Film, Universalia Film.

Latta, J. N. (1968) 'A Classified Bibliography on Holography and Related Fields (Second Half)' In: Journal of the SMPTE 77 (5) pp.540–580.

Le mépris (1963) Rome Paris Films, Les Films Concordia, Compagnia Cinematografica Champion.

Le petit soldat (1963) Les Productions Georges de Beauregard, Société Nouvelle de Cinématographie (SNC).

Malkiewicz, K. (2008) Film Lighting: Talks with Hollywood’s Cinematographers and Gaffers. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Marat/Sade (1967) Marat Sade Productions, Royal Shakespeare Company.

Mullen, D. (2012) History of Hard and Soft Lighting. At: https://cinematography.com/index.php?/forums/topic/58560-history-of-hard-and-soft-lighting/ (Accessed 24/08/2022).

Mullen, D. (2017) When did soft light become popular?. At: https://www.rogerdeakins.com/lighting-2/when-did-soft-light-become-popular/ (Accessed 30/08/2022).

Murnau, F. W. (1925) Der letzte Mann. IMDb ID: tt0015064.

Nicholson, W. F. (2010) 'Cinematography and character depiction' In: Global Media Journal - African Edition 4 (2) pp.196–211. At: https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC34942 (Accessed 23/08/2022).

Nogueira, R. (1977) 'Burel and Bresson' Translated by Milne, T. In: Monthly Film Bulletin 46 (1) Winter/1977 p.18. At: https://www.proquest.com/docview/740638071/citation/1EE347DFED6F43F2PQ/1 (Accessed 16/11/2022).

Oliver! (1968) Romulus Films, Warwick Film Productions.

Persona (1967) AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Petrie, D. (2018) 'A Changing Visual Landscape: British Cinematography in the 1960s' In: Journal of British Cinema and Television 15 (2) pp.204–227. At: https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.3366/jbctv.2018.0415 (Accessed 23/08/2022).

Petrie, D. J. (1996) The British Cinematographer. (1st Edition) London: BFI Publishing.

Pickpocket (1959) Compagnie Cinématographique de France.

Piepergerdes, B. J. (2007) 'Re-envisioning the nation: Film neorealism and the postwar Italian condition' In: ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 6 (2) pp.231–257.

Roger Deakins (2013) Controlling Bounced light. At: https://web.archive.org/web/20130313034308/http://www.deakinsonline.com/forum2/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=2228 (Accessed 20/12/2022).

Roger Deakins (2018) Hard Lights Combined With Soft Lights. At: https://www.rogerdeakins.com/lighting-2/hard-lights-combined-with-soft-lights (Accessed 07/03/2020).

Roma città aperta (1945) Excelsa Film.

Salomon, M. (2008) 'David Watkin – 1925-2008' In: La Lettre AFC 175 At: https://www.afcinema.com/David-Watkin-1925-2008.html (Accessed 20/01/2023).

Salt, B. (1992) Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis. (2nd ed.) Starword. At: https://archive.org/details/filmstyletechnol0000salt (Accessed 19/11/2022).

Schaefer, D. and Salvato, L. (2013) Masters of Light: Conversations with Contemporary Cinematographers. (s.l.): University of California Press.

Shiel, M. (2006) Italian neorealism: rebuilding the cinematic city. London New York: Wallflower.

Skyfall (2012) Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Columbia Pictures, Danjaq.

Sperduti nel buio (1914) Morgana Films.

Temple, M. and Witt, M. (2018) The French Cinema Book. (s.l.): Bloomsbury Publishing.

The Foundry (2020) The Art of Lighting: A history through time | Foundry. At: https://www.foundry.com/insights/film-tv/art-of-lighting-history (Accessed 05/09/2022).

The Knack ...and How to Get It (1965) Woodfall Film Productions.

The Matrix (1999) Warner Bros., Village Roadshow Pictures, Groucho Film Partnership.

Tom Jones (1963) Woodfall Film Productions.

Umberto D. (1952) Dear Film, Rizzoli Film, Produzione Films Vittorio De Sica. At: https://www.kanopy.com/en/ucreative/watch/video/112951

Wagstaff, C. (2007) Italian Neorealist Cinema: An Aesthetic Approach. (s.l.): University of Toronto Press.

Walsh, M. (1977) 'Rome, Open City. The Rise to Power of Louis XIV: Re-evaluating Rossellini' In: Jump Cut 15 pp.13–15. At: https://archive.org/details/sim_jump-cut_1977-07_15/page/15/mode/2up

Watkin, D. (2008) Was Clara Schumann a Fag Hag?: v.2: The Second Volume of an Autobiography Mainly, But Not Entirely, About the Film Business. (2nd ed.) England: Scrutineer Publishing.

Williams, B. (2008) Using Space lights. 24/01/2008 At: https://www.webofstories.com/people/billy.williams/34?o=SH (Accessed 25/01/2023).

Appendix A: A definition of realism

“First, it should project a slice of life, it should appear to enter and then leave everyday life. As ‘reality’ it should not use literary adaptations but go for the real. Second, it should focus on social reality: on the poverty and unemployment so rampant in post-war Italy. Third, in order to guarantee this realism, dialogue and language should be natural – even to the point of keeping to the regional dialects. To this effect also, preferably non-professional actors should be used. Fourth, location shooting rather than studio should prevail. And, finally, the shooting should be documentary in style, shot in natural light, with a hand-held camera and using observation and analysis.” (Hayward, 2017:235)

Appendix B: Soft Lite Discription

The light took the “form of a large sheet-metal box about three feet square on the open side, and with a very irregular interior surface painted matt white. Long quartz-iodine lamp tubes shone onto this surface from behind a narrow baffle that stopped them radiating light directly forward, and after a number of reflections from the white walls, the light emerged from the front opening of the box as a non-directional glow: indeed very like the light emerging through a north-facing window of rather small size.” (Salt, 1992:255)